Edited by Simon Bakke

Science communication is not a field many scientists hold in high regard, since it is not within the common confines of the academic or career industry. Scientists are not encouraged to interact with people outside of their field unless it benefits them. When it comes to science communication, I want to understand what speaking to the public about science entails — even if it may not pertain to their area of expertise — and to develop these skills. I believe communities would be more focused on the development of science if we could show them that science is more fun than frightening.

Dr. Joe Palca was the perfect person to introduce me to science communication. Joe did not realize what science communication was until long into his career. In 1982, Joe was completing his dissertation at the University of California Santa Cruz on sleep psychology when he saw an advertisement for the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellowship. This fellowship was focused on training scientists to strengthen their connection with journalists. Not enthralled with his research, he knew he did not want to stay in academia and wanted to try something new. Joe decided to give the fellowship a try; it was an opportunity to explore something new that valued his degree without constraining him to a laboratory.

“The part of grad school I really liked was teaching and working with students,” Joe said. “[The fellowship] was everything grad school was not — it was different every day.”

I was inspired as he explained how eager people were to meet him and the other fellows. I liked that scientists were able to speak to those outside of their field who listened and respected them for being scientists. When he returned to graduate school, he knew he wanted to switch careers, but proudly finished his Ph.D.

His goal was to be a television science communicator, but he knew he needed experience.

He was suggested by an AAAS Mass Media Fellow to take a writing test to be a vacation relief writer for the ABC station on San Francisco KGO. He took the test on Thursday, and on Friday he received a call asking him to start Monday. He assured me that anyone could be a science communicator, that all they had to was give it a try.

“Just take a swing. I don’t know if I wrote prize-winning stuff that first week, but I did OK, and that led to another week,” Joe said. I believe this is true; some people are afraid to take the first step towards a career in science communication, but the outcomes are rewarding.

Within a few years, he achieved his goal of becoming a television science communicator. Unfortunately, he developed a distaste for local news.

“Local news is very much dominated by sports and weather and gore. I didn’t really care for that,” Joe said.

Again, he switched careers. He was offered a job with Nature through his connections from when he was a Mass Media Fellow, and switched again to working at Science for a few years. He made the final career change to National Public Radio (NPR), where he has worked for the past 26 years. I was surprised he left reputable companies like Nature and Science, but pleased when he said, “I think it’s a good thing I left. I found myself happier with a news organization that reached the public, not just the science, so that was very satisfying.”

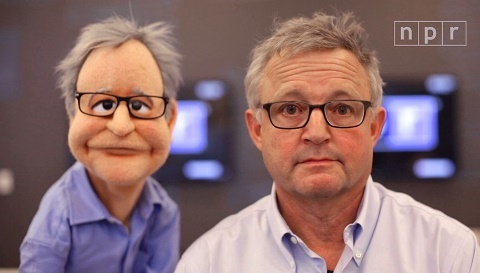

After reading, watching and listening to a few of his pieces on NPR (occasionally accompanied by the puppet in the photo), I noticed a majority of them were based on Astronomy, NASA and other topics. I was intrigued because he earned his Ph.D. in Sleep Psychology. So I asked: what’s it like writing in a field without any previous expertise and how do you overcome the obstacle of both learning and communicating it?

He explained he believes writing in a field that is not in your subject of expertise is actually easier, because you’re less constrained to know all the details. Though some think only scientists can become effective communicators, Joe does not.

“I believe non-scientists bring a lot of attributes to the table, and one of them is the ability to understand what a non-scientist doesn’t understand,” Joe said.

For scientists, one of the hardest things of getting into journalism is learning not to be an expert in what you are writing. Joe explained it helps to know the scientific method, and it helps to know the kind of questions scientists try to answer, but to know the details of the subject is not particularly helpful, because scientists can get caught up on the details.

What Joe said resonated with me. I later pondered the countless times I lost sight of what I was saying because I was too caught up in the details. His next example made it even clearer for me: sometimes, you need to ask the obvious.

“If you’re a sleep researcher and you ask what Stage Four sleep is, they’re going to ask, ‘what kind of sleep researcher are you?’ [It’s] awkward if you [already] know the answer, but you still have to ask bc it’s not your story — it’s their story.”

I never thought about it like that.

He tells starting science journalists that it is easier to write about things you do not know, since you are not as constrained by the things you needed to leave out to get your story across.

Many scientists, like myself, believe that science communication can be daunting. However, after speaking to Joe, I understand now that the hardest step is the first. Joe’s ambition to become a Mass Media fellow provided many opportunities for him. I did not realize until speaking to Joe that it is easier for some people to write about something outside of their expertise. Scientists need to be open to the idea of delving into fields that are not their own. By having confidence, passion, and ambition, they can become effective science communicators and help shape the future.

Leave a Reply