12/3/2020

0 Comments

By Stephanie Batalis

You’re stuck in the waiting room at the doctor’s office, and there isn’t a single copy of US weekly in sight. The TV is trapped on a loop about cold and flu season. Your only options for entertainment? A copy of The Journal of Physiology, and the nondescript doctor’s office art on the wall.

Here’s some free advice I learned early in grad school: pick up the science journal. Science journals are treasure troves of really cool stuff, discovered by asking life’s big questions. The articles within can help anyone learn more about an interesting topic or verify a scientific claim from social media. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, being able to assess scientific literature for yourself also means being able to stay informed and understand the recommended guidelines from health experts.

Journal articles are highly technical reports of cutting-edge science that are usually targeted to other experts. However, they aren’t just for scientists! In fact, a push to make journal articles open-access means that we have more access to these first-hand reports than ever before. Here, I’ll break down each section of a journal article to help you navigate the coolest new science and develop insights about the world around you.

Anatomy of Journal Article

Most journal articles follow a standard format: abstract, introduction, results, materials and methods, and discussion.

Abstract

Think of the abstract like a menu outside the door of a restaurant. The abstract gives you just enough information to decide whether to keep reading or move on. An abstract summarizes the whole paper in a single paragraph, including the most important findings and a brief explanation of what they mean.

Ask: Is this topic something that I’m interested in reading more about?

Introduction (Sometimes called Background)

Once you’ve made the decision to keep reading, the introduction section gives a “big picture” view of why this study was done. A good introduction clearly sets up two categories: What’s Known and What’s Unknown.

What’s Known explains what we already know; it usually involves a summary of research that has already been done in this area of science. A summary of the entire field would fill the whole journal, so this section is usually a selection of information that’s most relevant to this particular study. That means that even the background information can be a little dense for non-experts. That’s okay, because the overall goal is to get a general idea of the topic at hand.

What’s Unknown explains the current gaps in knowledge and why it’s important to find answers. The introduction usually ends by identifying the Big Science Question: the driving force behind the research.

Ask: What’s the big question that this study is trying to answer?

Results

Data, data, and more data. I actually recommend skipping this section for now. That’s because the individual scientific fields can get so niche that even scientists can have difficulty understanding technical data outside of their narrow area of expertise. As a biochemist, for example, I am unfamiliar with most of the techniques used in immunology papers. For this reason, I’m going to suggest putting this section on the back burner until after you’ve read the discussion section (More on that later!).

The Results section is usually divided into subsections for each experiment or finding. These sections are packed with information including the rationale or question, a hypothesis, a brief explanation of the experimental setup, and a description of the results. These results are represented in figures, which help readers to visualize the data. Figures can include anything from microscope pictures to graphs and are accompanied by a figure legend that describes the graphic.

Materials and Methods

The materials and methods section is the “how-to” guide for the study. This section is (and should be!) highly technical because it’s a step-by-step protocol for every experiment in the study. Skip this unless you want to know the technical details. Note – sometimes this section is placed before the Results or after the Discussion.

Discussion/Conclusions

The Discussion section (sometimes called Conclusion) is just that – a discussion about the research, its implications, and why we should care. Most discussion sections are “triangle-shaped” – they start specific and then get more general.

Restate: The conclusion starts specific by restating the research question and the main findings. This reminds the reader of what the study was trying to achieve and presents the results in the context of the main question.

Interpretation: After restating what the question and results were, the discussion expands upon those findings by interpreting what the results might mean. In other words, this section discusses how the results answer the question. How do these results fit into the bigger picture? Did they reveal something new?

Interpreting the results might mean proposing some sort of model. A model is a way to describe the patterns that the scientists observed in one “big picture” representation. However, it’s important to remember that these models are only one possible explanation out of many. This is because of a fundamental truth of science: the What’s Unknown category is ever-growing. Scientists are careful not to exaggerate or over-interpret their work because they know that there is always more to learn. This is why journal articles use words like “suggest” or “indicate” instead of “prove”. While a news story may say that a scientific discovery is a “miraculous breakthrough” or “revolutionary cure”, these words are inappropriate in a journal article.

Big Picture: Finally, the conclusion looks through a wide-angle lens by addressing how this work impacts the world outside of its niche scientific corner. For example, the results may change how we treat a disease or think about the makeup of the universe. This section also focuses on what comes next by suggesting new questions to follow up on.

I mentioned earlier that we would revisit the Results section after we had gotten a feel for how the experimental data impacts the big picture. Pick one or two findings that you’re particularly interested in, and focus on understanding how the data led to the authors’ conclusions and whether you agree with their interpretation.

Ask: Did the study answer the big question? Do the conclusions make sense given the data? Did this work highlight other big questions to follow up on?

Conflicts of Interest

Journals require scientists to declare any funding, employment, or financial interests that influence the objectivity of the research. This statement is usually found on the first or last page of the article, or right before the references.

References

Most scientific discoveries are based on decades of previous research. The References section cites every previous publication that is mentioned in the article. If there was background information in the article that interested you, this is a great place to look for your next read!

A Roadmap

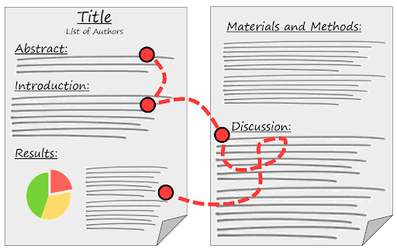

Now that we’ve dissected the anatomy of a journal article, here’s my guide to tackling one yourself.

- Check out the Abstract to decide if you want to keep reading

- Skim the Introduction to get the main idea and identify the “Big Science Question”

- Skip to the Discussion for the important results and what they mean

- Go back to the Results section to check out any data that caught your attention

- Hit the Materials and Methods if you want to know how a specific experiment was done

- Follow up – check out the References or look up other research if you want to know more about the topic

Need a place to start? Try sciencedirect.com for a huge selection of open-access, peer-reviewed journal articles that you can read anywhere. But first, a word of warning: not all scientific journals are created equal. Scientific journals are ranked by a metric called an “Impact Factor.” While not perfect, impact factors give a general measure of a journal’s importance within its field. Watch out for journals with low impact factors or worse, no impact factor at all. These may be predatory journals – publications that publish papers without peer review for a fee. Journals should report their impact factors, and you can search a list of predatory journals and publishers here.

Enjoy your journey into the world of science literature – without the doctor’s office waiting room.

Leave a Reply