11/11/2020

0 Comments

By Brooke N. Dulka; @IsRewriting

“How do you engage in science communication?” This is a question I posed to a group of academics during a breakout session at the virtual meeting of the Pavlovian Society in early September. Not surprisingly, that initial question was met mostly with silence from this group of psychologists and neuroscientists. Zoom fatigue? I wondered. However, after sharing some of my own tactics, the conversation began to pick up. One researcher gave a great example of how, although they don’t do a lot of non-academic article writing, they find that engaging in science-related discussions on social media is one way to reach people outside of their academic circles. Another person brought up NerdNite, an event where researchers give short talks to a more general audience in an informal setting.

We even completed an activity meant to simplify ideas and reduce jargon by describing your research in a sentence using words with no more than two syllables. Overall, it was a productive discussion, and before I knew it our hour was up. However, this breakout session brought to light many problems with the state of science communication within the academic community.

Scientists are indeed interested in increasing science communication and outreach.

So, while many scientists are interested in science communication, there appears to be little incentive from the larger academic community to actually engage in the activity.

One of the largest problems that these scientists (from trainees to senior investigators) face is support of their communication endeavors. Trainees often do not feel that their mentors support activities outside of research (although this is not always true). Early career researchers worry that by engaging in science communication they will not be taken seriously. There is also the ‘service’ aspect that e we can consider. For instance, does science communication count as service and thus increase the likelihood of being granted tenure? Will science communication be viewed favorably by funding agencies? Unfortunately, for many researchers at all stages, the answer to this question appears to be ‘no’ or, at best, ‘sometimes.’

One of the largest problems that these scientists (from trainees to senior investigators) face is support of their communication endeavors.

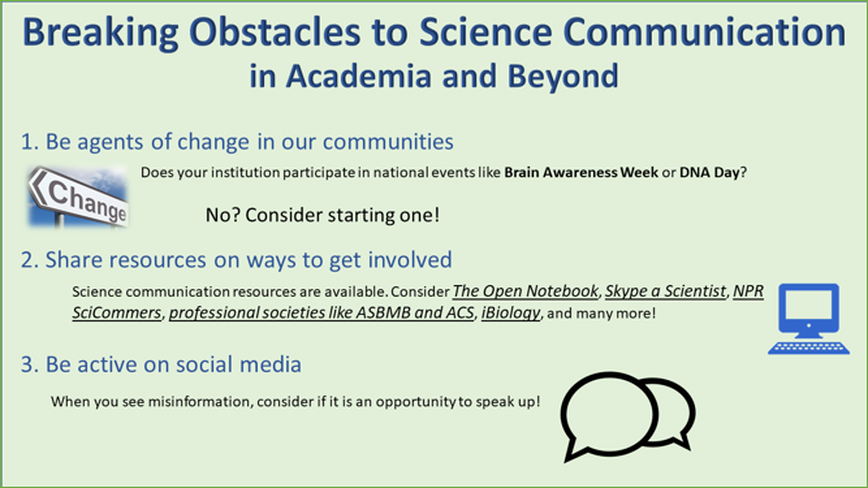

While this seems like a bleak outlook, I believe there is — in fact — more than a glimmer of hope on the horizon. This was particularly evident during the Pavlovian Society’s breakout session. We brainstormed ways that we can all, despite the obstacles, become more involved in science communication. Here are our top 3 approaches: First, we talked about how we can be agents of change within our own universities to increase science communication and outreach locally, for instance, if your university doesn’t already participate in outreach events such as Brain Awareness Week be the person who starts it!. Second, we shared resources to learn more, such as The Open Notebook, and get more involved, such as with Skype a Scientist. Finally, we discussed how we can be more active on social media; for instance, when misinformation presents itself on platforms such as Facebook — we can speak up and help inform our family and friends about critical scientific topics such as climate change, vaccinations, and COVID-19.

Three ways to break obstacles to science communication

If we all take these steps we can, as a collective, affect great change within our communities. Be the change you want to see within academia and the world so that we, as scientists and communicators, can increase public trust in science and inspire the next generation to do the same.

About the Author: Brooke N. Dulka

Brooke N. Dulka, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee where she studies memory. She is also an avid science writer and editor. In her free time, Brooke likes to drink tea and read science fiction. Follow her on Twitter @IsRewriting!

Leave a Reply