In our column, we’ve discussed ways to teach science communication in the classroom through lectures and classroom exercises. We’ve talked about the helpful do’s and don’ts in teaching SciComm in a classroom setting. In this article, we will highlight certain methods that were successful in the COVID-19 pandemic-related science communication.

In our last article, we discussed ways in which scientific research has helped advance the field of science communication. We introduced this concept in our previous blog post on evidence-based SciComm. As we explained in our post, and have learned through the COVID-19 pandemic, this is a relatively new field that still has a long way to go.

The pandemic, however, has provided us with an opportunity to informally evaluate science communication techniques. Throughout the pandemic, people around the world required outreach efforts to reach every corner of the globe. Scientists that followed the foundational findings of evidence-based SciComm were able to successfully advocate for science throughout the pandemic.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, effective SciComm that speaks to everyone has been important. So, what lessons have we learned from the past 16 months? Below, we will look at some of the methods that three top scientists involved in COVID-19 pandemic communication employed to further their messaging. While “seeing what works and doesn’t work” isn’t exactly tried-and-true science, it is the core of tried-and-true problem solving.

Remember that, at the end of the day, effective SciComm is all about your audience.

1. Prof. Akiko Iwasaki, Professor of Immunobiology, Yale School of Medicine

Prof. Iwasaki’s research helped shape patient care during the coronavirus pandemic. Prof. Iwasaki shifted her research to focus primarily on the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 just before the pandemic hit the United States. She is of the firm belief that public education and scientific literacy are key ingredients in slowing down the spread of the coronavirus pandemic.

To this end, Prof. Iwasaki has been prominently communicating the science behind the coronavirus. When asked about the strategies that worked, Prof. Iwasaki reminded followers to strive to use evidence-based messaging, be accessible and accurate, and also acknowledge limitations and defer questions to other experts, wherever applicable. She also reminded followers to remain calm when practicing SciComm.

2. Dr. Ian Mackay, virologist at the University of Queensland

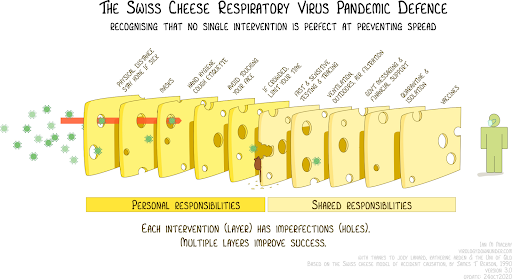

Dr. Mackay is best known for his “Swiss cheese model” of the pandemic depicted here.

As you can tell from the image, he was a prominent spokesperson for the need to use multiple “layers” in COVID-19 prevention, and used the cheese swiss model to communicate the importance of a multi-faceted approach required to control the pandemic virus. He provided us with plenty of advice for this article.

In his response to our question, he highlighted that regularity was important during the crisis. This included providing regular detailed updates on events. Authenticity was also crucial for his pandemic communications. More specifically, he suggested using voices that are “human and real” and communicating with calmness. He adds:

Prof. MacKay also talks about the importance of getting information from trusted, familiar faces, managing the public relations aspect inherent to COVID-19 communications.

3. Prof. Peter Hotez of Baylor University School of Medicine wears many hats

Peter Hotez is one of the most well-known COVID-19-related science communicators in the United States. He can frequently be seen on Fox News, MSNBC, CNN, and other media outlets talking about the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite being a tropical disease scientist and doctor, he’s able to communicate science to a diverse audience.

In fall 2020, Sheeva was hosting the @IAmSciComm account on Twitter and asked him for advice on explaining why people should stay home for Thanksgiving 2020 to mitigate the spread. His advice? “Try to balance realism and hope.”

In his communication, he puts his audience at the center of his communication, focusing on their concerns whilst also highlighting why COVID-19 (and COVID-19 prevention) is relevant to their lives.

Prof. Hotez has also been speaking about the rise of the anti-science movement in the United States and the anti-vaccine movement. In the video below, he explains the role scientists can play in providing a solution to the anti-science and anti-vaccine movements by encouraging trust in science and engaging with the public.

More specifically, he highlights that “as scientists we are invisible. We’re too focused on grants and papers and writing and speaking for each other that we’ve lost our ability and interest in reaching the public.” He adds that it is our responsibility to fix this and get scientists more involved in speaking to the public.

As we mentioned in our previous post, people aren’t persuaded by scientists spouting a list of facts. Instead, they are looking for a human connection in the form of emotions. These emotions can be negative or positive but must elicit a response in your audience.

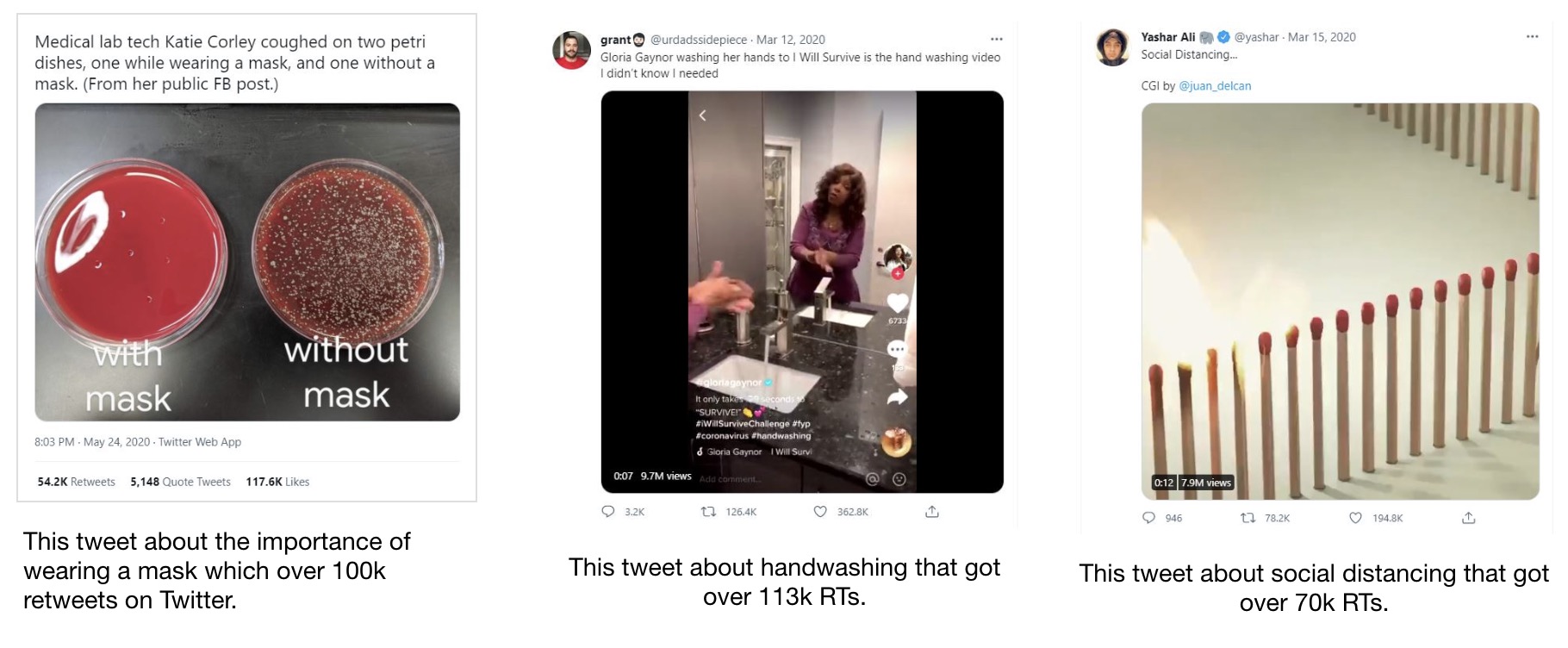

Below are some quick examples of pandemic SciComm that were incredibly popular on Twitter. As you will see, none of these science communications involved repeating everyday facts but clearly illustrated the importance of prevention strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

None of these tweets included “boring” scientific facts. You will not find a shred of actual data or an academic science citation in these articles. They simply, without many words, relayed a COVID-19 prevention strategy-related message clearly, simply, and persuasively.

Despite the many successes that SciComm professionals saw in their COVID-19 related communications, experts’ SciComm only went so far. Prof. Michael Berg of Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts explores the factors behind why some people follow COVID-19 guidelines while others largely ignore them.

In his research, Prof. Berg created a survey to examine patterns in the relationship between people’s health beliefs and behaviors to identify the factors that were most strongly associated with following prevention guidelines at the outset of the pandemic.

His research suggested that messages intended to calm the public may have inadvertently changed both perceptions and behaviors leading some people to take fewer precautions. Closing of schools persuaded people to take the pandemic and associated safety measures more seriously. The other emerging factor was the degree to which people viewed doctors and scientists as influential in their health outcomes. Prof. Berg’s research indicates that the more people believe such individuals play a meaningful role in their health, the more likely they are to listen to them. This means that messages where political leaders appeared potentially hurt engagement in prevention behavior.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we’d never needed such large-scale science communication efforts before. That’s why it’s a perfect time to assess what’s been working and what hasn’t. Clearly, some things have worked, with 67% of Americans getting at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Some things also have not worked, because the United States fell short of its goal of vaccinating 70% of its people before the July 4th holiday.

It’s time to take stock of what worked and what didn’t in pandemic science communication. Our lives depend on it.

Leave a Reply